The earliest mention of Atlas Iron that I have found is the announcement of the formation of the company in the Real Estate Record, 7 Feb 1891, p199. It took me a while to track this down, but I was recently able to get a good photo from the original publication thanks to the archives of the New York Public Library.

Their advertisement appeared later in that same issue:

Atlas Iron's incorporation was also announced in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on 12 Feb, and in The Engineering Record and the Engineering News on 14 Feb.

Showing posts with label Atlas Iron. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Atlas Iron. Show all posts

Sunday, May 14, 2017

Saturday, March 25, 2017

The Men of Atlas Iron

I've been curious about the men who worked together at Atlas Iron. Henry Williams had no expertise in building, and he joined forces with three younger men who did in order to start the company. I've discovered that those other three men - Philip Raqué, Frank Harrison and Frederick Youngs - all worked at Union Iron Works just prior to founding Atlas Iron. They very likely worked on the Columbia Building, which was the third skeleton-framed building in the city, and brought that knowledge with them to Atlas Iron.

As they formed their company, Henry Williams was 52, Philip Raqué was 35, Frank Harrison and Frederick Youngs were both 23, and Henry's son Frederick Williams was 22. I've also discovered that Frank Harrison, Fred Youngs and Fred Williams lived within a block of each other for a short time - more on that below.

Henry C. Williams was the company's president and put up most of the money for the venture. He was born in Lower Sandusky, Ohio in 1838. His parents both passed away while he was young. He later followed his older brother to New York City. He served in the Civil War, and then had a very successful career as a stock and bond broker. He and his wife Mary E. Harrison had two sons: Frederick in 1868 and Henry Jr. in 1869. His son Frederick described him as "one of those successful 'self-made' men we used to read about; a good, honest, kind-hearted, generous man; clean-living, courteous and chivalrous to a degree not often seen to-day [in 1945],--a gentleman at heart as well as in manners. He was extremely punctilious in keeping his word,--always a little ahead of time for an appointment,--never failing to pay a bill when promised,--and expecting the same in others."

Henry sold his seat on the New York Stock Exchange and retired right around the time he turned 49. However, he "was of too active a disposition to settle down and live on his income." He began looking for a new business venture, which ultimately became Atlas Iron Construction.

After Atlas Iron went out of business at the end of 1895, Henry Williams retired to his vacation home in Castine, Maine. The failure of the company - and his own finances, which he used to try and save it - came as a heavy blow, and his family believed that contributed to his death the following September.

Philip E. Raqué was the company's vice president and engineer. He was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1855. He was in the second graduating class of the Stevens Institute of Technology in 1876, earning a degree in mechanical engineering. His thesis was titled "Design for Iron Foundery", and he was in the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. He and his wife Eliza Ferritt had at least one son, Arthur, in 1888. They may have had another son in 1896, and I have seen mention of a daughter. It has been difficult to find clear information about his family or life.

After Atlas Iron, Philip Raqué continued to work as an engineer in New York and New Jersey. He worked on the Ansonia Apartment Hotel, the Newark Armory and the Jersey City Armory, among other projects.

Frank S. Harrison was the company's secretary, engineer and superintendent. He was also the cousin of Henry Williams' first wife, Mary Harrison. Frank was born in New Haven, Connecticut in 1867, grew up there and attended Yale's Sheffield Scientific School. He graduated in 1886 at the age of 18 (it was a three-year program and, while he was young for his class, this was not unprecedented). His focus was on civil engineering and his thesis was on cantilever bridges.

Frank worked as an engineer for several years throughout New England. Fred Williams described him as "a genius as an engineer", and wrote of his inventing an advanced derrick and devising the roof of an armory drill hall, both for Atlas Iron. He and Harriet H. Eyster were married in 1892 and they had three daughters: Elizabeth in 1894, Helen in 1896 and Margaret in 1901. He was "good natured, easy going, and had the knack of getting along well with the men on the various jobs, as well as with everybody else."

After Atlas Iron, Frank Harrison moved to Halltown, West Virginia where he became managing partner and eventually president of Eyster & Son, his father-in-law's paper box board company.

Frederick T. Youngs was the company's treasurer and a builder by trade. He was born in Stamford, Connecticut in 1867, the eldest son out of eleven children. By 1880, his family was living in New Rochelle, New York. I don't know where he went to school. He and Kate C. Davis married in 1889. They had a son, William, that same year and another, Frederick Jr., in 1894.

Frederick's father was William H. W. Youngs (sometimes listed as Henry Walmsley Youngs), a prominent architect at the time in New York City. Most notably, he and his partner William A. Cable - as Youngs & Cable - designed Aldrich Court and the Columbia Building. Atlas Iron ended up working on a number of buildings designed by Youngs and/or Cable.

After Atlas Iron, Fred Youngs shifted his career focus from steel construction to general construction. He partnered with Leonard Jacob Jr. as Jacob & Youngs, and devoted much of his career to building the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

Frederick H. Williams is also worth mentioning here. He was my

great-great-grandfather, and he wrote many of the details which have

been passed down through the family about Atlas Iron, Henry Williams

(his father) and Frank Harrison.

Fred was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1868. He graduated from Yale in 1891. Having no career plans yet except to enter business, he took a job at Atlas Iron. His duties included copying and typing letters, checking prices and information, and sometimes answering the telephone (which he tried to avoid). When not busy with his own work he would watch and learn from the men in the drafting room and sometimes assist them with their blueprints. He was later put in charge of the company payroll. He and Alice E. Corbett married in 1893. They had two sons and a daughter: Marshall in 1894, Mary in 1896 and Harrison in 1901.

After Atlas Iron, Fred Williams moved to Binghamton, New York where he had a long career teaching high school history, civics and government.

Fred Williams wrote that he lived near Frank Harrison, and in checking for details I found that not only did they live within a block of each other for a short time, but that Fred Youngs lived nearby as well. The Harrisons lived briefly at #335 Lafayette Ave. in Brooklyn before moving to New Jersey. The Williams family lived at #345 Lafayette and the Youngs family lived at either #343 or #341. Meanwhile, Henry C. Williams lived about a dozen blocks away at #28 Lafayette Ave., and Philip Raqué lived in Jersey City.

In my research, I've only come across a few other names of men involved with the Atlas Iron Construction Company. They were:

Thomas O. Horton, a civil engineer who graduated from Sheffield Scientific School in 1891.

S. J. Johnston, an engineer.

Edward Raqué, Philip's younger brother, an assistant engineer.

And a Mr. Shulte, who had charge of the company's Jersey City workshop.

Selected Sources:

Philip Raqué obituary, New York Sun, 24 Nov 1936, via FindAGrave.

For Frank Harrison: Obituary Record of Yale Graduates, 1920-21.

I am grateful to Diane Gravlee for sharing her research on Frederick and William Youngs, and to the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen for providing details on Frederick Youngs (who was a member).

Family papers.

As they formed their company, Henry Williams was 52, Philip Raqué was 35, Frank Harrison and Frederick Youngs were both 23, and Henry's son Frederick Williams was 22. I've also discovered that Frank Harrison, Fred Youngs and Fred Williams lived within a block of each other for a short time - more on that below.

|

| Henry C. Williams with his sons, Fred (left) and Henry (right), circa 1879 |

Henry sold his seat on the New York Stock Exchange and retired right around the time he turned 49. However, he "was of too active a disposition to settle down and live on his income." He began looking for a new business venture, which ultimately became Atlas Iron Construction.

After Atlas Iron went out of business at the end of 1895, Henry Williams retired to his vacation home in Castine, Maine. The failure of the company - and his own finances, which he used to try and save it - came as a heavy blow, and his family believed that contributed to his death the following September.

Philip E. Raqué was the company's vice president and engineer. He was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1855. He was in the second graduating class of the Stevens Institute of Technology in 1876, earning a degree in mechanical engineering. His thesis was titled "Design for Iron Foundery", and he was in the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. He and his wife Eliza Ferritt had at least one son, Arthur, in 1888. They may have had another son in 1896, and I have seen mention of a daughter. It has been difficult to find clear information about his family or life.

After Atlas Iron, Philip Raqué continued to work as an engineer in New York and New Jersey. He worked on the Ansonia Apartment Hotel, the Newark Armory and the Jersey City Armory, among other projects.

Frank S. Harrison was the company's secretary, engineer and superintendent. He was also the cousin of Henry Williams' first wife, Mary Harrison. Frank was born in New Haven, Connecticut in 1867, grew up there and attended Yale's Sheffield Scientific School. He graduated in 1886 at the age of 18 (it was a three-year program and, while he was young for his class, this was not unprecedented). His focus was on civil engineering and his thesis was on cantilever bridges.

Frank worked as an engineer for several years throughout New England. Fred Williams described him as "a genius as an engineer", and wrote of his inventing an advanced derrick and devising the roof of an armory drill hall, both for Atlas Iron. He and Harriet H. Eyster were married in 1892 and they had three daughters: Elizabeth in 1894, Helen in 1896 and Margaret in 1901. He was "good natured, easy going, and had the knack of getting along well with the men on the various jobs, as well as with everybody else."

After Atlas Iron, Frank Harrison moved to Halltown, West Virginia where he became managing partner and eventually president of Eyster & Son, his father-in-law's paper box board company.

Frederick T. Youngs was the company's treasurer and a builder by trade. He was born in Stamford, Connecticut in 1867, the eldest son out of eleven children. By 1880, his family was living in New Rochelle, New York. I don't know where he went to school. He and Kate C. Davis married in 1889. They had a son, William, that same year and another, Frederick Jr., in 1894.

Frederick's father was William H. W. Youngs (sometimes listed as Henry Walmsley Youngs), a prominent architect at the time in New York City. Most notably, he and his partner William A. Cable - as Youngs & Cable - designed Aldrich Court and the Columbia Building. Atlas Iron ended up working on a number of buildings designed by Youngs and/or Cable.

After Atlas Iron, Fred Youngs shifted his career focus from steel construction to general construction. He partnered with Leonard Jacob Jr. as Jacob & Youngs, and devoted much of his career to building the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

|

| Frederick H. Williams as an undergraduate |

Fred was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1868. He graduated from Yale in 1891. Having no career plans yet except to enter business, he took a job at Atlas Iron. His duties included copying and typing letters, checking prices and information, and sometimes answering the telephone (which he tried to avoid). When not busy with his own work he would watch and learn from the men in the drafting room and sometimes assist them with their blueprints. He was later put in charge of the company payroll. He and Alice E. Corbett married in 1893. They had two sons and a daughter: Marshall in 1894, Mary in 1896 and Harrison in 1901.

After Atlas Iron, Fred Williams moved to Binghamton, New York where he had a long career teaching high school history, civics and government.

Fred Williams wrote that he lived near Frank Harrison, and in checking for details I found that not only did they live within a block of each other for a short time, but that Fred Youngs lived nearby as well. The Harrisons lived briefly at #335 Lafayette Ave. in Brooklyn before moving to New Jersey. The Williams family lived at #345 Lafayette and the Youngs family lived at either #343 or #341. Meanwhile, Henry C. Williams lived about a dozen blocks away at #28 Lafayette Ave., and Philip Raqué lived in Jersey City.

In my research, I've only come across a few other names of men involved with the Atlas Iron Construction Company. They were:

Thomas O. Horton, a civil engineer who graduated from Sheffield Scientific School in 1891.

S. J. Johnston, an engineer.

Edward Raqué, Philip's younger brother, an assistant engineer.

And a Mr. Shulte, who had charge of the company's Jersey City workshop.

Selected Sources:

Philip Raqué obituary, New York Sun, 24 Nov 1936, via FindAGrave.

For Frank Harrison: Obituary Record of Yale Graduates, 1920-21.

I am grateful to Diane Gravlee for sharing her research on Frederick and William Youngs, and to the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen for providing details on Frederick Youngs (who was a member).

Family papers.

Monday, October 3, 2016

Cantilevers Continued

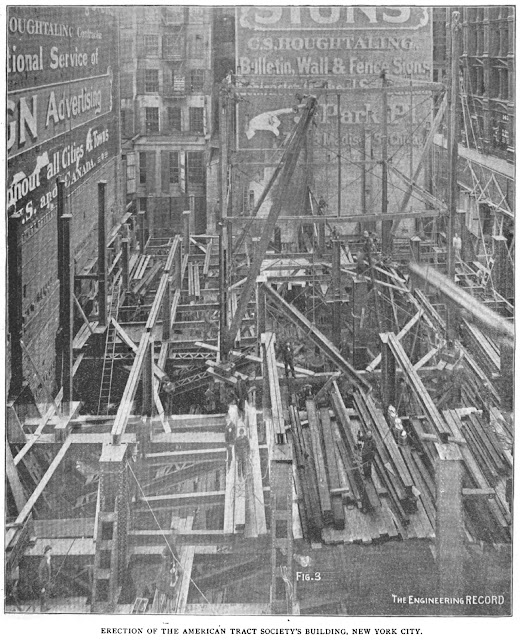

I've just come across another article about the construction of the American Tract Society Building. It included two photos of the great cantilevers, as they were being installed in the sub-basement:

The article discussed many details of the construction of the building. It revealed this about the advanced derrick which was used: "The best test of the structure's capacity, which has been made, was when loads of 7, 6 and 5 tons were swung on three corners at the same time. Lighter loads have been swung from all [five of] the booms at once."

Source:

The Railroad Gazette, vol 26, 14 Dec 1894, p850-852.

The article discussed many details of the construction of the building. It revealed this about the advanced derrick which was used: "The best test of the structure's capacity, which has been made, was when loads of 7, 6 and 5 tons were swung on three corners at the same time. Lighter loads have been swung from all [five of] the booms at once."

Source:

The Railroad Gazette, vol 26, 14 Dec 1894, p850-852.

Wednesday, August 3, 2016

Terrapins and Cantilevers

I recently stopped by the American Tract Society Building with my brother, hoping to find out if any historical or architectural tours are ever given. The doorman said no, but was glad to chat about the building's history. When I mentioned that there used to be a restaurant on the roof he immediately pulled out a photocopy of a lunch menu from 1901. The prices range from 5 cents for a cup of coffee or a Charlotte Russe, to a full dollar for the fanciest dish: Diamond Back Terrapin a la Maryland.

After we told the doorman about our family's connection to the building, he said that there are some large steel columns on the sub-basement level which now serves as a parking garage. Luckily, we were able to go and take a look at this steel work... the first time I have seen steel which I know Atlas Iron put in place.

In two areas, foundations for the columns could not be provided. Therefore, pairs of cantilevers were constructed on either side of a pair of columns (seen above). The weight from one column in the building above is transferred to the two other column footings. The cantilevers are 40 feet long and 12 feet high above the shoe. The steel columns were fireproofed with four inches of brickwork, and the cantilevers with wire lathing and heavy-gauged mortar an inch thick. There are at least 500 tons of steel on the sub-basement level alone.

If you look carefully, you can spot these same cantilevers in the construction photo which I previously posted. It was a thrill to see them in person.

Sources:

"American Tract Society's 20-Story Office Building, New York City", Engineering News, vol 32, no 26, 27 December 1894, p526-529.

"Erection of American Tract Society's Building, New York", The Engineering Record, vol 31, no 3, 15 December 1894, p44-47.

After we told the doorman about our family's connection to the building, he said that there are some large steel columns on the sub-basement level which now serves as a parking garage. Luckily, we were able to go and take a look at this steel work... the first time I have seen steel which I know Atlas Iron put in place.

In constructing this building, the lot was dug down to

36 feet below street level. Piles of American Spruce were driven into

the ground from there, to a depth of 10 to 40 feet. These were capped

with concrete and then granite slabs, on which the steel columns rest.

The cast iron shoes for some of the columns (seen above) are about five feet square. The granite slabs beneath them are ten inches thick and guaranteed to bear a load of two and a half tons per square inch.

In two areas, foundations for the columns could not be provided. Therefore, pairs of cantilevers were constructed on either side of a pair of columns (seen above). The weight from one column in the building above is transferred to the two other column footings. The cantilevers are 40 feet long and 12 feet high above the shoe. The steel columns were fireproofed with four inches of brickwork, and the cantilevers with wire lathing and heavy-gauged mortar an inch thick. There are at least 500 tons of steel on the sub-basement level alone.

If you look carefully, you can spot these same cantilevers in the construction photo which I previously posted. It was a thrill to see them in person.

Sources:

"American Tract Society's 20-Story Office Building, New York City", Engineering News, vol 32, no 26, 27 December 1894, p526-529.

"Erection of American Tract Society's Building, New York", The Engineering Record, vol 31, no 3, 15 December 1894, p44-47.

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

The Offerman Water Tank

I came across two listings in the Real Estate Record which state that Atlas Iron built a water tank for the Offerman Building in Brooklyn, around the time of its completion in 1893.

This tank intrigued me. The building was commissioned and owned by Henry Offerman. At first it was referred to as the Wechsler Building, because it housed clothiers S. Wechsler and Brother (who later moved to one of the storefronts at 532-540 Fulton St.). The building still stands at 503-513 Fulton Street, and it still has a large water tank on its roof. As always, I wanted to know more. I also wondered - knowing this was highly unlikely - whether the current tank could possibly be the same one that Atlas Iron put in place.

After searching for as many details and photos as I could, and then visiting the building to see the tank in person, I'm convinced that it can't be the same one. However, it seems that a tank of similar size has always been in that spot on the roof. A photo from 1930 and a photo from 1941 both show tanks which match the one standing there today. A tax map from around 2003 actually shows two tanks, one in that spot marked "20,000 gal" while the other was a smaller tank at the center of the building's Duffield Street facade (since removed). I'm inclined to think that the larger tank is the one which Atlas Iron built, but I can't even be sure of that.

While researching this, I learned that there are only three companies in the city which work on water tanks today. Most are made of wood, but steel is occasionally used (and is then encased in wood to help keep the tank cool). I contacted all three companies to see if they had any records of working on this tank, and only one responded to say that they didn't.

In the end, this tank interested me because it was something new and different from the other things that I've been researching.

Side note: I've recently added a few more details to some of my other posts about Atlas Iron's projects. Check for my additions as comments on the Morris Building, 532-540 Fulton St. and the Brooklyn Post Office Annex.

Sources:

Real Estate Record and Builder's Guide, 31 Dec 1892, p894; 4 March 1893, p348.

Landmarks Preservation Commission designation listing for the Offerman Building.

"The Other Downtown", New York Times, 22 Nov 2013.

This tank intrigued me. The building was commissioned and owned by Henry Offerman. At first it was referred to as the Wechsler Building, because it housed clothiers S. Wechsler and Brother (who later moved to one of the storefronts at 532-540 Fulton St.). The building still stands at 503-513 Fulton Street, and it still has a large water tank on its roof. As always, I wanted to know more. I also wondered - knowing this was highly unlikely - whether the current tank could possibly be the same one that Atlas Iron put in place.

After searching for as many details and photos as I could, and then visiting the building to see the tank in person, I'm convinced that it can't be the same one. However, it seems that a tank of similar size has always been in that spot on the roof. A photo from 1930 and a photo from 1941 both show tanks which match the one standing there today. A tax map from around 2003 actually shows two tanks, one in that spot marked "20,000 gal" while the other was a smaller tank at the center of the building's Duffield Street facade (since removed). I'm inclined to think that the larger tank is the one which Atlas Iron built, but I can't even be sure of that.

While researching this, I learned that there are only three companies in the city which work on water tanks today. Most are made of wood, but steel is occasionally used (and is then encased in wood to help keep the tank cool). I contacted all three companies to see if they had any records of working on this tank, and only one responded to say that they didn't.

In the end, this tank interested me because it was something new and different from the other things that I've been researching.

Side note: I've recently added a few more details to some of my other posts about Atlas Iron's projects. Check for my additions as comments on the Morris Building, 532-540 Fulton St. and the Brooklyn Post Office Annex.

Sources:

Real Estate Record and Builder's Guide, 31 Dec 1892, p894; 4 March 1893, p348.

Landmarks Preservation Commission designation listing for the Offerman Building.

"The Other Downtown", New York Times, 22 Nov 2013.

Monday, May 23, 2016

Smith & Gray's or the Building Next Door?

I discovered another of the buildings that Atlas Iron worked on, not by accident but thanks to an accident which happened on an unnamed work site. The process of researching this one has taken some unusual twists and turns.

In autumn of 1892, a new building was going up in Brooklyn. The cellar was still open and Atlas Iron had just about completed the iron framework for the first floor. Some of their men were moving a derrick and knocked over a pile of bricks... which fell into the cellar where one or several of the bricks struck a worker named Thomas Reilly. He took Atlas Iron to court over the incident. While the nature of his injuries aren't specified in the records, they were referred to as being very serious. In June of 1895, a jury awarded Mr. Reilly $5000 in damages (half of what he sought; the amount translates to roughly $150,000 today). Atlas Iron filed several appeals, but the original judgement was always upheld.

I learned about this court case several months ago. What I wanted to know was where the accident took place. No street name or even neighborhood was given for the building site. The court records include testimony from a witness who said the building was "about 100 feet square," and clearly describes it as "next to Smith & Gray's." A newspaper article said that the accident happened while Atlas was "putting up the iron skeleton work in Smith & Gray's big building in November, 1892." So... which building were they working on? (I suppose they could have even worked on both, but have operated on the premise that it was just one.)

To complicate matters, Smith, Gray & Company owned half a dozen buildings in Brooklyn. Without further clues to guide my search, I was stumped for a long while. I was inclined to trust the court record over the newspaper article, but I didn't know which buildings to look at. I recently decided to try and solve the mystery.

I started by searching again for details on the court case, and came across a new record with three key pieces of information. First, Thomas Reilly was employed by a T. J. or P. J. Castin & Co, though searches on these names turned up nothing other than references back to this same trial. Second, the date of the accident was given as the 15th of September 1892. Finally, the building site was described as being on Fulton Street. This narrowed things down considerably, to one of Smith & Gray's buildings and its neighbors.

Smith, Gray & Company produced ready-made clothes for boys and children, and they were highly successful. In 1888 they had an eight story building constructed on the irregular corner of Nevins St., Flatbush Ave. and Fulton St. in Brooklyn's downtown shopping district. This building had a tower with a prominent clock - a local landmark.

On the 28th of February 1892, a major fire broke out which destroyed this building and damaged several others around it. The clock tower split... half of it falling on three adjacent buildings on Fulton Street and the other half damaging the elevated railroad tracks which ran along Flatbush Avenue. The total damage from the fire was estimated at around $750,000.

Armed with this information, I searched the Real Estate Record's listings of building projects in Brooklyn during 1892. By early August of that year, plans were filed to construct a new Smith & Gray building - ten stories tall - on that corner lot. When I reached the listings for September, I thought that I wouldn't find anything else (recall that the accident was said to take place on the 15th of September). However, I continued on and found the answer.

By mid-September, plans had been filed for a new building at numbers 532-540 Fulton Street, just next door to Smith & Gray's. This site was owned by the estate of the late John D. Cocks and the contractors were... P. J. Carlin & Co. This is where everything clicked together for me. I can easily see how a handwritten Carlin in the court record could be mistakenly transcribed as Castin, and this backs up the testimony that the accident happened at a work site adjacent to Smith & Gray's.

What's more, Google Street View shows both of the buildings still in place, though they have both suffered over the years.

Smith & Gray's new building only climbed three stories rather than the intended ten. At some point, a seventeen story clock tower was added on the Nevins Street side, again standing as a local landmark. In 1941, the tower was damaged by a fire in the adjacent building on Nevins Street. It was declared unsafe and cut down to seven stories, which is how it stands today.

Meanwhile, I've gathered quite a bit of information about 532-540 Fulton Street. It seems that John Cocks purchased those five lots before the Civil War for $800 apiece. At the end of 1891, a row of four-story brick buildings stood there. Plans were well under way to replace them with a new building encompassing all five addresses. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle gave a lengthy description of the project. It was hoped to be an attractive six-story building in granite and terra cotta. An unnamed, "large New York furniture firm" was expected to occupy the new building, though the contracts were not final. The architects were Ross & Marvin. Work was expected to begin in the spring.

The five buildings were still occupied at the time of the fire, and at least three of them were heavily damaged. The construction plans were changed. By the time they were filed again, A. W. Ross was listed alone as the architect. I presume this is the same Ross, but haven't found any other details about him or his erstwhile partner. The plans filed by September called for a three-story brick and terra cotta building with a tin roof and iron cornice. After the unfortunate accident involving Mr. Reilly, the building was completed and opened for business by the spring of 1893.

The first tenants to move in were indeed a furniture and carpet firm: Murray, Conway & Company. The building was divided into three storefronts at first. Some of the other businesses there over the next two decades were clothiers, a lamp store, and piano stores. A Woolworth's five-and-dime store opened in one storefront in 1895, and by 1911 had expanded to take up all five storefronts. They remained there until the early 1940s.

The Rosemont Dance Hall opened on the second floor, probably in the 1920s, and the third floor was rented out as storage space. Fire struck once again on the 19th of February 1942. This one started in the dance hall and spread up through the third floor - which the Eagle declared "destroyed" - and the roof (the Eagle even had a photo of this fire). The ground floor and adjacent buildings were damaged by water and smoke, but not by flames. Damage from this fire was estimated at $250,000.

While I have not found evidence to back this up, I believe the building's third story was removed after that fire. By September of that year, the Nevins Bowling Center opened on the second floor, boasting 20 "alleys."

Since the building was still standing, I decided to visit. I wanted to get a closer look and take photos (which I intended to include in this post). However, when I made the trek to Brooklyn this past weekend I was in for a surprise... the building has been torn down! Only an empty lot remains there at the moment. It seems the building was razed just last December, and plans have been filed to put a 19-story retail and office building on the site. Therefore, here's a photo from Google Street View which shows the building in September 2014.

Sources:

New York State Reporter, v64, p332.

New York Supplement, v38, p485.

Real Estate Record and Builder's Guide, 26 Dec 1891, p828; 6 Aug 1892, p195; 17 Sept 1892, p367; 22 June 1895, p1057.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 15 Dec 1891, p6; 29 Feb 1892, p4 and 6; 14 Aug 1941, p2; 19 Feb 1942, p1.

The Sun (New York), 14 June 1895, p5.

The New York Times, 20 Feb 2005.

Smith, Gray & Company Building Designation Report, Landmarks Preservation Commission, 2005. This is primarily about Smith & Gray's first building, on Broadway in Williamsburg. It also gives good details of their company history and other buildings.

Brownstoner blog: 532-540 Fulton Street and 2-4 Nevins Street (Smith & Gray's building). These two posts have additional photos.

In autumn of 1892, a new building was going up in Brooklyn. The cellar was still open and Atlas Iron had just about completed the iron framework for the first floor. Some of their men were moving a derrick and knocked over a pile of bricks... which fell into the cellar where one or several of the bricks struck a worker named Thomas Reilly. He took Atlas Iron to court over the incident. While the nature of his injuries aren't specified in the records, they were referred to as being very serious. In June of 1895, a jury awarded Mr. Reilly $5000 in damages (half of what he sought; the amount translates to roughly $150,000 today). Atlas Iron filed several appeals, but the original judgement was always upheld.

I learned about this court case several months ago. What I wanted to know was where the accident took place. No street name or even neighborhood was given for the building site. The court records include testimony from a witness who said the building was "about 100 feet square," and clearly describes it as "next to Smith & Gray's." A newspaper article said that the accident happened while Atlas was "putting up the iron skeleton work in Smith & Gray's big building in November, 1892." So... which building were they working on? (I suppose they could have even worked on both, but have operated on the premise that it was just one.)

To complicate matters, Smith, Gray & Company owned half a dozen buildings in Brooklyn. Without further clues to guide my search, I was stumped for a long while. I was inclined to trust the court record over the newspaper article, but I didn't know which buildings to look at. I recently decided to try and solve the mystery.

I started by searching again for details on the court case, and came across a new record with three key pieces of information. First, Thomas Reilly was employed by a T. J. or P. J. Castin & Co, though searches on these names turned up nothing other than references back to this same trial. Second, the date of the accident was given as the 15th of September 1892. Finally, the building site was described as being on Fulton Street. This narrowed things down considerably, to one of Smith & Gray's buildings and its neighbors.

Smith, Gray & Company produced ready-made clothes for boys and children, and they were highly successful. In 1888 they had an eight story building constructed on the irregular corner of Nevins St., Flatbush Ave. and Fulton St. in Brooklyn's downtown shopping district. This building had a tower with a prominent clock - a local landmark.

On the 28th of February 1892, a major fire broke out which destroyed this building and damaged several others around it. The clock tower split... half of it falling on three adjacent buildings on Fulton Street and the other half damaging the elevated railroad tracks which ran along Flatbush Avenue. The total damage from the fire was estimated at around $750,000.

|

| This sketch is from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 29 February 1892. |

Armed with this information, I searched the Real Estate Record's listings of building projects in Brooklyn during 1892. By early August of that year, plans were filed to construct a new Smith & Gray building - ten stories tall - on that corner lot. When I reached the listings for September, I thought that I wouldn't find anything else (recall that the accident was said to take place on the 15th of September). However, I continued on and found the answer.

By mid-September, plans had been filed for a new building at numbers 532-540 Fulton Street, just next door to Smith & Gray's. This site was owned by the estate of the late John D. Cocks and the contractors were... P. J. Carlin & Co. This is where everything clicked together for me. I can easily see how a handwritten Carlin in the court record could be mistakenly transcribed as Castin, and this backs up the testimony that the accident happened at a work site adjacent to Smith & Gray's.

What's more, Google Street View shows both of the buildings still in place, though they have both suffered over the years.

Smith & Gray's new building only climbed three stories rather than the intended ten. At some point, a seventeen story clock tower was added on the Nevins Street side, again standing as a local landmark. In 1941, the tower was damaged by a fire in the adjacent building on Nevins Street. It was declared unsafe and cut down to seven stories, which is how it stands today.

|

| The Flatbush Ave. facade of the old Smith & Gray Building. #532-540 Fulton St. is barely visible to the right. Photo courtesy of Google. |

Meanwhile, I've gathered quite a bit of information about 532-540 Fulton Street. It seems that John Cocks purchased those five lots before the Civil War for $800 apiece. At the end of 1891, a row of four-story brick buildings stood there. Plans were well under way to replace them with a new building encompassing all five addresses. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle gave a lengthy description of the project. It was hoped to be an attractive six-story building in granite and terra cotta. An unnamed, "large New York furniture firm" was expected to occupy the new building, though the contracts were not final. The architects were Ross & Marvin. Work was expected to begin in the spring.

The five buildings were still occupied at the time of the fire, and at least three of them were heavily damaged. The construction plans were changed. By the time they were filed again, A. W. Ross was listed alone as the architect. I presume this is the same Ross, but haven't found any other details about him or his erstwhile partner. The plans filed by September called for a three-story brick and terra cotta building with a tin roof and iron cornice. After the unfortunate accident involving Mr. Reilly, the building was completed and opened for business by the spring of 1893.

The first tenants to move in were indeed a furniture and carpet firm: Murray, Conway & Company. The building was divided into three storefronts at first. Some of the other businesses there over the next two decades were clothiers, a lamp store, and piano stores. A Woolworth's five-and-dime store opened in one storefront in 1895, and by 1911 had expanded to take up all five storefronts. They remained there until the early 1940s.

The Rosemont Dance Hall opened on the second floor, probably in the 1920s, and the third floor was rented out as storage space. Fire struck once again on the 19th of February 1942. This one started in the dance hall and spread up through the third floor - which the Eagle declared "destroyed" - and the roof (the Eagle even had a photo of this fire). The ground floor and adjacent buildings were damaged by water and smoke, but not by flames. Damage from this fire was estimated at $250,000.

While I have not found evidence to back this up, I believe the building's third story was removed after that fire. By September of that year, the Nevins Bowling Center opened on the second floor, boasting 20 "alleys."

Since the building was still standing, I decided to visit. I wanted to get a closer look and take photos (which I intended to include in this post). However, when I made the trek to Brooklyn this past weekend I was in for a surprise... the building has been torn down! Only an empty lot remains there at the moment. It seems the building was razed just last December, and plans have been filed to put a 19-story retail and office building on the site. Therefore, here's a photo from Google Street View which shows the building in September 2014.

|

| #532-540 Fulton St. Photo courtesy of Google. |

Sources:

New York State Reporter, v64, p332.

New York Supplement, v38, p485.

Real Estate Record and Builder's Guide, 26 Dec 1891, p828; 6 Aug 1892, p195; 17 Sept 1892, p367; 22 June 1895, p1057.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 15 Dec 1891, p6; 29 Feb 1892, p4 and 6; 14 Aug 1941, p2; 19 Feb 1942, p1.

The Sun (New York), 14 June 1895, p5.

The New York Times, 20 Feb 2005.

Smith, Gray & Company Building Designation Report, Landmarks Preservation Commission, 2005. This is primarily about Smith & Gray's first building, on Broadway in Williamsburg. It also gives good details of their company history and other buildings.

Brownstoner blog: 532-540 Fulton Street and 2-4 Nevins Street (Smith & Gray's building). These two posts have additional photos.

Labels:

Atlas Iron

Location:

540 Fulton St, Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA

Friday, April 22, 2016

An Armory Drill Hall Roof

In writing about our family history, my great-great-grandfather Frederick Williams gave several details about his mother's cousin, Frank Harrison. Frank was Atlas Iron's Secretary and Superintendent and a "genius as an engineer." One noteworthy tale which Fred preserved was this:

After a few months of doing research on the company, I found a single mention in a newspaper article which seemed to provide the answer. It stated that they worked on the Ninth Regiment Armory, which was built between 1894 and 1896, on West 14th Street.

The Ninth Regiment (today the 244th Air Defense Artillery Regiment) can trace its history back to the War of 1812. They served in the Civil War as the 83rd New York Volunteers. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, they rented quarters on West 26th Street above a stable and carriage house. After the founding of New York City's Armory Board in 1884, the regiment (like many others) began petitioning for a new home. They would be one of the last regiments of the time to actually receive a new armory.

After a long, slow process, a site was chosen on 14th Street. It was in the middle of the block between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, and it ran through to 15th Street. The Twenty-Second Regiment's armory which occupied most of this site was razed to make way for the new building. The Twenty-Second had moved to their brand new armory at Broadway and 67th Street in 1892.

A design competition was held, and the plans entered by the architecture firm of William A. Cable and Edward A. Sargent were chosen. This fact is what makes me fairly confident that Atlas Iron did work on the Ninth Regiment Armory. William Cable had previously been the partner of William H. W. Youngs, father of one of the founders of Atlas, and Atlas Iron worked on several Youngs & Cable projects.

So, what about the impressive drill hall? Sources vary on the exact dimensions, but it was roughly 220 feet long and 185 feet wide (around 41,000 square feet). The center of the arches stood around 64 feet tall. This was not unprecedented. The famous Seventh Regiment Armory, completed over a decade before, has a 55,000 square foot drill hall. Several other armories which were built in and around the city prior to 1894 had similarly large drill halls. I find it hard to believe that engineers would have declared it an impossible feat at that time. Perhaps Fred, who was writing about this in the 1940s, conflated his recollections of Atlas Iron's work and press coverage of the groundbreaking Seventh Regiment Armory. This is not to say that the Ninth Regiment's armory and drill hall did not also deserve - and receive - plenty of praise.

The Ninth Regiment had one of the smallest building plots for an armory in the city at the time, just over an acre (one newspaper said it covered 46,000 square feet). To maximize space for the drill hall on that site, two levels of rooms were suspended between the giant steel trusses, one stacked on top of the other. A skylight was built into the roof.

The armory was completed at the end of the summer of 1896. In addition to military drills, the space was used for civic events; concerts, exhibitions, bicycling, indoor baseball games and other sporting events were all held there. The building stood until 1969, when it was torn down to make way for the Forty-Second Division's new headquarters.

Sources:

Souvenir - Opening of the Armory - Ninth Regiment, N.G., N.Y. (22 Feb 1897).

The Armory Board, 1884-1911 (1912, New York City Armory Board).

Proceedings of the Commissioners of the Sinking Fund of the City of New York (1894-96).

The Sun (New York), 7 Oct 1894 and 4 Sept 1895.

New-York Tribune, 28 Feb 1894 and 8 April 1896.

Family papers.

New York's Historic Armories: An Illustrated History, by Nancy L. Todd (2006). This is an excellent book, if you're interested in learning more about arsenals and armories throughout New York City and State.

America's Armories: Architecture, Society, and Public Order by Robert M. Fogelson (1989).

Daytonian in Manhattan: "The Lost 1895 9th Regiment Armory - 125 West 14th Street".

Exterior photo from Library of Congress (and posted on Daytonian in Manhattan).

Drill hall photo from New York State Military Museum (and included in Todd's book).

"He also devised great roof construction for the drill hall of a N.Y. Armory spanning an entire city block. The engineers said it could not be done, so it was quite an accomplishment for our company as the newspapers told the story."This anecdote, more than anything else, is what prompted me to look into the history of Atlas Iron. It conjures a notion of great achievements in building... and it omits the most important piece of information. Which armory did they actually work on?

After a few months of doing research on the company, I found a single mention in a newspaper article which seemed to provide the answer. It stated that they worked on the Ninth Regiment Armory, which was built between 1894 and 1896, on West 14th Street.

After a long, slow process, a site was chosen on 14th Street. It was in the middle of the block between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, and it ran through to 15th Street. The Twenty-Second Regiment's armory which occupied most of this site was razed to make way for the new building. The Twenty-Second had moved to their brand new armory at Broadway and 67th Street in 1892.

A design competition was held, and the plans entered by the architecture firm of William A. Cable and Edward A. Sargent were chosen. This fact is what makes me fairly confident that Atlas Iron did work on the Ninth Regiment Armory. William Cable had previously been the partner of William H. W. Youngs, father of one of the founders of Atlas, and Atlas Iron worked on several Youngs & Cable projects.

So, what about the impressive drill hall? Sources vary on the exact dimensions, but it was roughly 220 feet long and 185 feet wide (around 41,000 square feet). The center of the arches stood around 64 feet tall. This was not unprecedented. The famous Seventh Regiment Armory, completed over a decade before, has a 55,000 square foot drill hall. Several other armories which were built in and around the city prior to 1894 had similarly large drill halls. I find it hard to believe that engineers would have declared it an impossible feat at that time. Perhaps Fred, who was writing about this in the 1940s, conflated his recollections of Atlas Iron's work and press coverage of the groundbreaking Seventh Regiment Armory. This is not to say that the Ninth Regiment's armory and drill hall did not also deserve - and receive - plenty of praise.

The Ninth Regiment had one of the smallest building plots for an armory in the city at the time, just over an acre (one newspaper said it covered 46,000 square feet). To maximize space for the drill hall on that site, two levels of rooms were suspended between the giant steel trusses, one stacked on top of the other. A skylight was built into the roof.

The armory was completed at the end of the summer of 1896. In addition to military drills, the space was used for civic events; concerts, exhibitions, bicycling, indoor baseball games and other sporting events were all held there. The building stood until 1969, when it was torn down to make way for the Forty-Second Division's new headquarters.

Sources:

Souvenir - Opening of the Armory - Ninth Regiment, N.G., N.Y. (22 Feb 1897).

The Armory Board, 1884-1911 (1912, New York City Armory Board).

Proceedings of the Commissioners of the Sinking Fund of the City of New York (1894-96).

The Sun (New York), 7 Oct 1894 and 4 Sept 1895.

New-York Tribune, 28 Feb 1894 and 8 April 1896.

Family papers.

New York's Historic Armories: An Illustrated History, by Nancy L. Todd (2006). This is an excellent book, if you're interested in learning more about arsenals and armories throughout New York City and State.

America's Armories: Architecture, Society, and Public Order by Robert M. Fogelson (1989).

Daytonian in Manhattan: "The Lost 1895 9th Regiment Armory - 125 West 14th Street".

Exterior photo from Library of Congress (and posted on Daytonian in Manhattan).

Drill hall photo from New York State Military Museum (and included in Todd's book).

Labels:

Atlas Iron

Location:

125 W 14th St, New York, NY 10011, USA

Saturday, February 13, 2016

Union Iron Works and the Columbia Building

Don't worry, I haven't forgotten which company I'm researching here. Please bear with me for a minute...

I got curious about how the founders of Atlas Iron might have met and decided to work together. As a reminder, the four gentlemen in question are Henry Williams, Philip Raqué, Frank Harrison and Frederick Youngs.

Frank Harrison was the cousin of Henry Williams' first wife, Mary Harrison. Mary passed away in 1878. By 1889, Henry and Frank both lived in Brooklyn so it's reasonable to imagine them being in contact with each other.

I did some research on all four men to see what else I could learn, and I found a really interesting connection...

Philip Raqué and Frank Harrison were both engineers, and in 1889 and '90 they both worked at a company called Union Iron Works.1 Founded in early 1889, Union Iron had a factory in Greenpoint and an office at 45 Broadway - a building called Aldrich Court. The company gained distinction for its involvement in putting up the third skeleton frame building in New York City: the Columbia Building.2

The Columbia was twelve stories tall and stretched from Broadway along Morris Street to Trinity Place (just a few doors down from Aldrich Court - both buildings were owned by the Aldrich estate). The plot was long but narrow. As The Sun reported:

Skeleton frame construction was slowly adopted in the city over the next several years, and it was a method used regularly by Atlas Iron. Philip Raqué and Frank Harrison seem to have gained excellent first-hand experience with this practice at Union Iron Works.

The connection doesn't end there, though. The Columbia building was designed by architects William Youngs and William Cable. Incidentally, they had designed Aldrich Court and also had their offices there.

William Youngs was the father of our Frederick Youngs. I haven't been able to find details on Frederick's education or where he was working prior to the founding of Atlas Iron. It's possible that he worked at his father's firm, where he could have been closely involved with the Columbia building as well, and would have known Philip and Frank. Even if he didn't work there, he might have known those men and that project.

I wonder if there was any further connection between these men. Perhaps William Youngs had been a client of Henry Williams during his days as a stock broker, for instance. Perhaps Henry simply met the other men through his cousin-in-law. In any case, he could have dropped by at Aldrich Court in 1890 to meet with two if not all three of the men who would join him in forming Atlas Iron, and they would have been working on and discussing the Columbia Building at the time.

Notes:

1. For Philip Raqué: Stevens Indicator, vol. 6, 1889, p161. For Frank Harrison: Yale University Obituary Record, 1921, p217.

2. "The First 'Skeleton' Building", Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide, 12 Aug 1899, p239. The first skeleton frame building in the city was the Tower Building, constructed in 1889, designed by Branford Gilbert. The second was the Lancashire Insurance Co. building, constructed in 1889-90, designed by J. C. Cady & Co.

3. "New Down-town Buildings", The Sun, 19 April 1891, p27.

Photo. Excerpt from "Broadway - Morris Street", 1894, from Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.

I got curious about how the founders of Atlas Iron might have met and decided to work together. As a reminder, the four gentlemen in question are Henry Williams, Philip Raqué, Frank Harrison and Frederick Youngs.

Frank Harrison was the cousin of Henry Williams' first wife, Mary Harrison. Mary passed away in 1878. By 1889, Henry and Frank both lived in Brooklyn so it's reasonable to imagine them being in contact with each other.

I did some research on all four men to see what else I could learn, and I found a really interesting connection...

Philip Raqué and Frank Harrison were both engineers, and in 1889 and '90 they both worked at a company called Union Iron Works.1 Founded in early 1889, Union Iron had a factory in Greenpoint and an office at 45 Broadway - a building called Aldrich Court. The company gained distinction for its involvement in putting up the third skeleton frame building in New York City: the Columbia Building.2

The Columbia was twelve stories tall and stretched from Broadway along Morris Street to Trinity Place (just a few doors down from Aldrich Court - both buildings were owned by the Aldrich estate). The plot was long but narrow. As The Sun reported:

To build solid masonry walls in compliance with the laws of the Building Bureau for a structure of that great height would have necessitated walls ten feet in thickness, and thus twenty feet of the ground space would have been required for walls on the basement and first floors, leaving only a little more than nineteen feet of available floor space.The president of Union Iron Works, P. Minturn Smith, convinced the owner of the Columbia lot that skeleton frame construction would be both safe and economical. Thus the building went up in 1890-91, with the walls of "the first story measuring only 2.8 feet."3

Skeleton frame construction was slowly adopted in the city over the next several years, and it was a method used regularly by Atlas Iron. Philip Raqué and Frank Harrison seem to have gained excellent first-hand experience with this practice at Union Iron Works.

The connection doesn't end there, though. The Columbia building was designed by architects William Youngs and William Cable. Incidentally, they had designed Aldrich Court and also had their offices there.

William Youngs was the father of our Frederick Youngs. I haven't been able to find details on Frederick's education or where he was working prior to the founding of Atlas Iron. It's possible that he worked at his father's firm, where he could have been closely involved with the Columbia building as well, and would have known Philip and Frank. Even if he didn't work there, he might have known those men and that project.

I wonder if there was any further connection between these men. Perhaps William Youngs had been a client of Henry Williams during his days as a stock broker, for instance. Perhaps Henry simply met the other men through his cousin-in-law. In any case, he could have dropped by at Aldrich Court in 1890 to meet with two if not all three of the men who would join him in forming Atlas Iron, and they would have been working on and discussing the Columbia Building at the time.

Notes:

1. For Philip Raqué: Stevens Indicator, vol. 6, 1889, p161. For Frank Harrison: Yale University Obituary Record, 1921, p217.

2. "The First 'Skeleton' Building", Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide, 12 Aug 1899, p239. The first skeleton frame building in the city was the Tower Building, constructed in 1889, designed by Branford Gilbert. The second was the Lancashire Insurance Co. building, constructed in 1889-90, designed by J. C. Cady & Co.

3. "New Down-town Buildings", The Sun, 19 April 1891, p27.

Photo. Excerpt from "Broadway - Morris Street", 1894, from Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.

Labels:

Atlas Iron

Location:

29 Broadway, New York, NY 10006, USA

Monday, January 25, 2016

The Brooklyn Post Office Annex

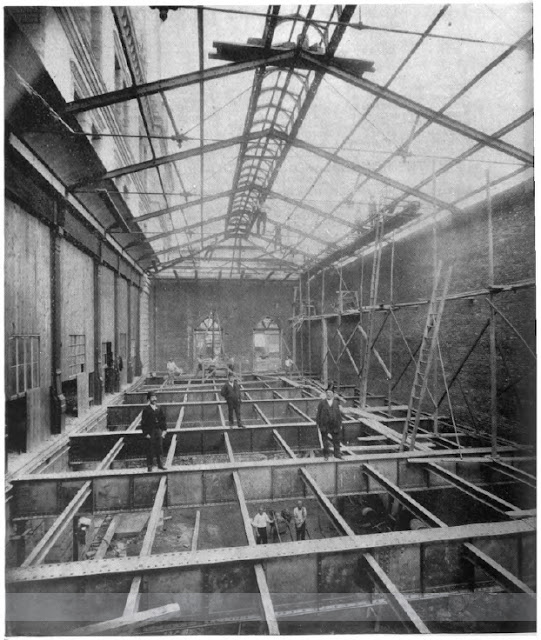

I recently came across this photograph, showing the Atlas Iron men putting up an annex for the Brooklyn Post Office.

The Brooklyn Federal Building - which stands today between Johnson St., Cadman Plaza East, Tillary St. and Adams St./Brooklyn Bridge Blvd. - is made up of two structures. The original, four-story building on the southern end of the block was designed to house Brooklyn's main post office and four courtrooms. Planning began in 1885, construction started in 1888, the exterior was finished in 1891 and the interior followed in 1892.

By early 1890, it was becoming apparent that the building would not be adequate. Legislation was introduced in Washington, D.C. by Congressman William C. Wallace in April, to allow a single-story annex to be built on the north side of the building. The annex would increase the working space of the post office by 5000 square feet. It would have a "roadway under [the] floor" on the Adams St. side, to serve as a loading dock for mail wagons. Its basement would house the steam heating and electric lighting machinery for the entire Federal Building - which could not be opened until these were in place. The bill was passed at the end of September.

Bids were finally taken for the construction of the annex in February 1891. The winning bid ($64,650) went to Bernard Gallagher, who had been the first contractor on the main building. It was meant to be completed by the start of May, but there were further delays. The government claimed that there were property boundary disputes to work out with neighbors, and newspapers claimed that the troubles were really financial: the Billion Dollar Congress having drained the Treasury.

The annex and Federal Building were finally completed and the post office was informally opened on 27 March 1892, under postmaster George J. Collins.

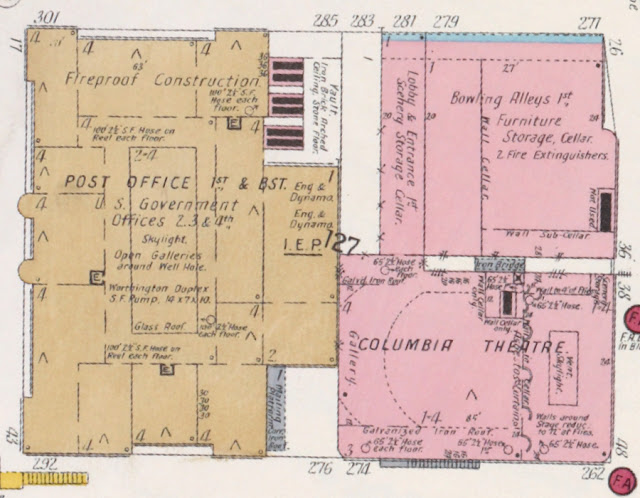

I have not been able to find a photo of the completed annex, but I did find an insurance map from 1904 which shows the footprint of the buildings on that block in detail. (In this map excerpt, north is to the right.)

By summer, a new problem presented itself. The annex had an all-glass roof, and with the sun shining down on the mailing division floor plus boilers working below them to power the main building's elevators, it became a sweatbox. Shades were finally added to the windows at the end of the summer. The following May, there was still talk of needing to protect "the eyes of the clerks employed in the annex" from the glaring sun.

The further history of the annex is rather unclear. The post office and other departments in the building faced increasing demands. More of the property north of the building may have been purchased in 1899. I have seen mentions of a new addition built in 1908, but haven't found any specifics on that.

The government purchased the remainder of the block, up to Tillary Street, around 1915. This held a pair of buildings which had operated together as the Columbia Theater, then briefly as a burlesque house called the Alcazar, and then returned to the name Columbia to present silent films. The second building served as the theater lobby and also housed a bowling alley and perhaps a bank after that. The Federal Building's supervising architect James Wetmore was later quoted in the Eagle saying, "we utilized first one building and then the other to provide space for the postoffice, and finally connected them with the main building by a temporary structure."

I haven't been able to determine whether the 1891 Annex, built by Gallagher and Atlas Iron, was replaced by any of this work or simply incorporated into it. In any case, the entire set of buildings (still referred to as "the annex") was torn down in 1929. This cleared the way for a seven-story addition, designed by Wetmore and built between 1930 and 1933, which takes up the northern part of the block and stands conjoined with the original Federal Building today.

Sources:

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, especially: 11 Apr 1890, 30 Sept 1890, 14 Oct 1890, 12 Feb 1891, 19 June 1891, 26 June 1891, 13 Sept 1891, 17 July 1892, 17 Aug 1892, 4 May 1894, 7 June 1908, 12 Jan 1913, 23 Oct 1928, 15 Oct 1929.

New York Times: 11 Feb 1891, 28 Mar 1892.

Catalog of the Second Annual Exhibition of the Department of Architecture of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences (1893).

Insurance Maps, Borough of Brooklyn, City of New York, Vol. 2 (Sanborn Map Co., 1904). From The New York Public Library.

The Brooklyn Federal Building - which stands today between Johnson St., Cadman Plaza East, Tillary St. and Adams St./Brooklyn Bridge Blvd. - is made up of two structures. The original, four-story building on the southern end of the block was designed to house Brooklyn's main post office and four courtrooms. Planning began in 1885, construction started in 1888, the exterior was finished in 1891 and the interior followed in 1892.

By early 1890, it was becoming apparent that the building would not be adequate. Legislation was introduced in Washington, D.C. by Congressman William C. Wallace in April, to allow a single-story annex to be built on the north side of the building. The annex would increase the working space of the post office by 5000 square feet. It would have a "roadway under [the] floor" on the Adams St. side, to serve as a loading dock for mail wagons. Its basement would house the steam heating and electric lighting machinery for the entire Federal Building - which could not be opened until these were in place. The bill was passed at the end of September.

Bids were finally taken for the construction of the annex in February 1891. The winning bid ($64,650) went to Bernard Gallagher, who had been the first contractor on the main building. It was meant to be completed by the start of May, but there were further delays. The government claimed that there were property boundary disputes to work out with neighbors, and newspapers claimed that the troubles were really financial: the Billion Dollar Congress having drained the Treasury.

The annex and Federal Building were finally completed and the post office was informally opened on 27 March 1892, under postmaster George J. Collins.

I have not been able to find a photo of the completed annex, but I did find an insurance map from 1904 which shows the footprint of the buildings on that block in detail. (In this map excerpt, north is to the right.)

By summer, a new problem presented itself. The annex had an all-glass roof, and with the sun shining down on the mailing division floor plus boilers working below them to power the main building's elevators, it became a sweatbox. Shades were finally added to the windows at the end of the summer. The following May, there was still talk of needing to protect "the eyes of the clerks employed in the annex" from the glaring sun.

The further history of the annex is rather unclear. The post office and other departments in the building faced increasing demands. More of the property north of the building may have been purchased in 1899. I have seen mentions of a new addition built in 1908, but haven't found any specifics on that.

The government purchased the remainder of the block, up to Tillary Street, around 1915. This held a pair of buildings which had operated together as the Columbia Theater, then briefly as a burlesque house called the Alcazar, and then returned to the name Columbia to present silent films. The second building served as the theater lobby and also housed a bowling alley and perhaps a bank after that. The Federal Building's supervising architect James Wetmore was later quoted in the Eagle saying, "we utilized first one building and then the other to provide space for the postoffice, and finally connected them with the main building by a temporary structure."

I haven't been able to determine whether the 1891 Annex, built by Gallagher and Atlas Iron, was replaced by any of this work or simply incorporated into it. In any case, the entire set of buildings (still referred to as "the annex") was torn down in 1929. This cleared the way for a seven-story addition, designed by Wetmore and built between 1930 and 1933, which takes up the northern part of the block and stands conjoined with the original Federal Building today.

Sources:

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, especially: 11 Apr 1890, 30 Sept 1890, 14 Oct 1890, 12 Feb 1891, 19 June 1891, 26 June 1891, 13 Sept 1891, 17 July 1892, 17 Aug 1892, 4 May 1894, 7 June 1908, 12 Jan 1913, 23 Oct 1928, 15 Oct 1929.

New York Times: 11 Feb 1891, 28 Mar 1892.

Catalog of the Second Annual Exhibition of the Department of Architecture of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences (1893).

Insurance Maps, Borough of Brooklyn, City of New York, Vol. 2 (Sanborn Map Co., 1904). From The New York Public Library.

Labels:

Atlas Iron

Location:

Adams St, Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA

Tuesday, November 17, 2015

The Morris Building, Under Construction

I've just come across two terrific photos of Atlas Iron work sites. I love this type of shot which actually shows something in progress.

Here is one of the two, showing the construction of the Morris Building (about which I have previously written).

The photo comes from an advertisement for Atlas Iron in the Catalog of the Second Annual Exhibition of the Department of Architecture of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences (1893).

Labels:

Atlas Iron

Location:

68 Broad St, New York, NY 10004, USA

Wednesday, November 4, 2015

St. Paul's M. E. Church

I recently had a chance to see some of the iron work which - I believe - Atlas Iron put in place. This was at the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew on the Upper West Side.

The church originated on Mulberry Street in 1834. After one previous move, the congregation decided in 1890 to move further north. A site was selected and Robert H. Robertson designed what was then called St. Paul's Methodist Episcopal Church (they later merged with nearby St. Andrew's). Construction took place between June 1895 and September 1897.

I found out that Atlas Iron was involved in this construction thanks to three mechanic's liens which were placed against the church, naming Atlas Iron as a secondary party. The liens - placed by Passaic Rolling Mill Co, Bethlehem Foundry and Machine Co, and Theodore Smith (who ran an iron works) - totaled $1184. They were all paid off.

During my research, I saw on the church's website that they participate in the annual Open House New York program, where sites around the city open their doors for architectural tours. In a grand stroke of luck, I saw this just a week before this year's event took place! So, I trekked into the city to visit and see what I could learn.

As soon as I explained what brought me there, I was introduced to their current architect, Skip Boling. Skip showed me around the building and helped look for any iron or steel structural elements. The most prominent of these are a set of cast iron columns in the basement, which hold up the sanctuary floor.

There are three rows of these columns. Two are out in the open in the social hall, and the third runs through the food pantry and kitchens (you can actually see a column from that third row, through the second window in the photo).

The entire basement went through a complete renovation several years ago, under Skip's design and direction. He told me that they stripped layers of paint from the iron columns and also uncovered nearby brick piers which support the building above. He decided to bring out the natural beauty of the original iron and brick to give character to the new social hall.

As we toured the rest of the building, we found metal work in several of the stairwells. I also had a chance to speak with the church's historian, Elizabeth Jensen, and their pastor, K Karpen. I was told that the sanctuary ceiling and the roof are both supported with steel. There may be additional steel work which is hidden and thus remains a mystery.

One intriguing possibility is the set of columns running along either side of the sanctuary. Made to look like ornately carved marble, these actually consist of a thin outer shell made of metal (providing the aesthetic look) and undoubtedly some type of structural column within.

Adding to the mystery is the fact that Atlas Iron went out of business in late 1895 or early 1896. While the liens indicate that they handled at least $1100 worth of metal from three different sources, I haven't come across any details about which specific parts of the church they worked on. I like to think that they put up the iron columns in the basement, and perhaps they worked on the columns on the sanctuary level as well, but we simply don't know. I wasn't able to find company names or markings on any of the metal work that I saw. I was still very glad to explore the church, talk to everyone there and imagine the possibilities.

A final side note: while researching St. Paul's, I ran across another distant relation. An article in the New York Tribune listed the church's trustees at the time of the construction. Among them was Phineas C. Lounsbury - the brother of an ancestor on my mother's side of the family. Atlas Iron was run by Henry C. Williams, an ancestor on my father's side. It's actually possible that Phineas and Henry knew each other, as they were both prominent bankers with connections to New York City.

For more on the renovation of the church's basement and other work that has been done recently, with photos and plans, see Skip Boling's website.

For more on the church's history, see their website.

The church originated on Mulberry Street in 1834. After one previous move, the congregation decided in 1890 to move further north. A site was selected and Robert H. Robertson designed what was then called St. Paul's Methodist Episcopal Church (they later merged with nearby St. Andrew's). Construction took place between June 1895 and September 1897.

I found out that Atlas Iron was involved in this construction thanks to three mechanic's liens which were placed against the church, naming Atlas Iron as a secondary party. The liens - placed by Passaic Rolling Mill Co, Bethlehem Foundry and Machine Co, and Theodore Smith (who ran an iron works) - totaled $1184. They were all paid off.

During my research, I saw on the church's website that they participate in the annual Open House New York program, where sites around the city open their doors for architectural tours. In a grand stroke of luck, I saw this just a week before this year's event took place! So, I trekked into the city to visit and see what I could learn.

As soon as I explained what brought me there, I was introduced to their current architect, Skip Boling. Skip showed me around the building and helped look for any iron or steel structural elements. The most prominent of these are a set of cast iron columns in the basement, which hold up the sanctuary floor.

There are three rows of these columns. Two are out in the open in the social hall, and the third runs through the food pantry and kitchens (you can actually see a column from that third row, through the second window in the photo).

As we toured the rest of the building, we found metal work in several of the stairwells. I also had a chance to speak with the church's historian, Elizabeth Jensen, and their pastor, K Karpen. I was told that the sanctuary ceiling and the roof are both supported with steel. There may be additional steel work which is hidden and thus remains a mystery.

One intriguing possibility is the set of columns running along either side of the sanctuary. Made to look like ornately carved marble, these actually consist of a thin outer shell made of metal (providing the aesthetic look) and undoubtedly some type of structural column within.

Adding to the mystery is the fact that Atlas Iron went out of business in late 1895 or early 1896. While the liens indicate that they handled at least $1100 worth of metal from three different sources, I haven't come across any details about which specific parts of the church they worked on. I like to think that they put up the iron columns in the basement, and perhaps they worked on the columns on the sanctuary level as well, but we simply don't know. I wasn't able to find company names or markings on any of the metal work that I saw. I was still very glad to explore the church, talk to everyone there and imagine the possibilities.

A final side note: while researching St. Paul's, I ran across another distant relation. An article in the New York Tribune listed the church's trustees at the time of the construction. Among them was Phineas C. Lounsbury - the brother of an ancestor on my mother's side of the family. Atlas Iron was run by Henry C. Williams, an ancestor on my father's side. It's actually possible that Phineas and Henry knew each other, as they were both prominent bankers with connections to New York City.

For more on the renovation of the church's basement and other work that has been done recently, with photos and plans, see Skip Boling's website.

For more on the church's history, see their website.

Sunday, October 18, 2015

Liens and Fires and Strikes, Oh My...

In 1891, the Atlas Iron Construction Company put up the iron framework for a building in downtown New Rochelle, New York for prominent local businessman George Ferguson. They then got into a lengthy dispute with Ferguson over the final payment and the quality of the work. If not for this dispute and the court records it generated, I wouldn't have even known that Atlas Iron worked on this building. It turns out to be a rather troubled story all the way through.

George Ferguson ran a grocery store which also offered such things as hardware, feed, bicycles and corsets. It was located on an L-shaped lot with one facade on Main Street and the other on Center Avenue (the building wrapped around another which was directly on the corner of Main and Center). He had the misfortune of having his store burn down not once, but twice.

The first fire claimed Ferguson's store and several other buildings in early September 1875. He rebuilt, using brick for his new store. The second fire occurred fifteen years later, at the start of November 1890. It too claimed several buildings. Fire companies from half a dozen nearby towns rallied to prevent the destruction of more of the downtown area. Papers gave estimates upwards of $225,000 for the total damage done. Ferguson's building was destroyed, along with furniture stored on the second floor in spaces he rented out to others. One mention in the court records says that Ferguson burned his hand in the fire, badly enough that he was still recovering the following June.

Once again intent on rebuilding, Ferguson hired the noted New York City architect William H. W. Youngs (of Youngs & Cable) to design a four-story brownstone building. Ferguson insisted that the new building needed to be strong enough to handle any sort of storage needs that he might have, especially on the second floor where he once again planned to rent out space. After drawing up the plans, William Youngs lobbied for Atlas Iron to be given the contract to construct the iron framework of the building. His son, Frederick Youngs, was Treasurer of the newly formed company - a connection which was not concealed from George Ferguson.

Atlas Iron did win the contract, and raised the building's framework during the spring and summer of 1891. There were some delays during the process, partly caused by an iron workers' strike which lasted through the month of May. The Housesmiths' Union called the strike in an attempt to have work hours reduced to eight hours per day while keeping their nine hour wage. Over four thousand men were involved. Fifty employers in New York City, Brooklyn and Jersey City joined together to resist the strike. Both sides thought that it would end quickly, but it dragged on until the union men gave in and returned to work on their old terms. This effectively ended the influence of the Housesmiths' Union. The impact on the Ferguson building site was that some of the iron columns came from the foundry of F. W. Davis & Brother, and others (much delayed) came from that of Francis Haas.

Upon completion of their part of the construction, Atlas Iron sent George Ferguson an invoice to settle their bill. This included $990 still owed on the contract, plus other charges and credits accumulated by both parties which reduced the invoice to just over $900. Ferguson refused to pay, disputing the additional charges and credits. After attempting in vain to settle their differences, Atlas Iron filed a mechanics' lien in January of 1892 to try and secure their final payment.

George Ferguson responded with a counterclaim, stating that the work had not been completed satisfactorily and that Atlas Iron and William Youngs had colluded against him, forcing him to accept inferior work. He sought damages for this loss of value to his building and for the delays in construction, plus the full amount of his additional charges. His claim came to a total of just over $4000. The court directed that the matter be heard by a referee - Walter Large, Esq. - who would make a ruling.

Much of the documented testimony from these proceedings focuses on the strength of the iron columns used in the building. The plans called for columns one inch thick. The Atlas Iron men insisted that they ordered the columns as specified, but that three-quarter inch columns were entirely sufficient for the building (it's unclear which thickness of column was actually ordered). George Ferguson and his head builder, David Meyers, recalled being concerned about the quality of the iron columns when they were delivered. The columns were put in place anyway and the building was completed and occupied. It was only during the course of the legal proceedings that holes were bored to measure the thickness of the columns (something not typically done upon delivery unless the buyer requested it), and they were found to be three-quarters of an inch thick. Other aspects of the construction and of the various additional costs on both sides were also disputed in front of the referee.