I got curious about how the founders of Atlas Iron might have met and decided to work together. As a reminder, the four gentlemen in question are Henry Williams, Philip Raqué, Frank Harrison and Frederick Youngs.

Frank Harrison was the cousin of Henry Williams' first wife, Mary Harrison. Mary passed away in 1878. By 1889, Henry and Frank both lived in Brooklyn so it's reasonable to imagine them being in contact with each other.

I did some research on all four men to see what else I could learn, and I found a really interesting connection...

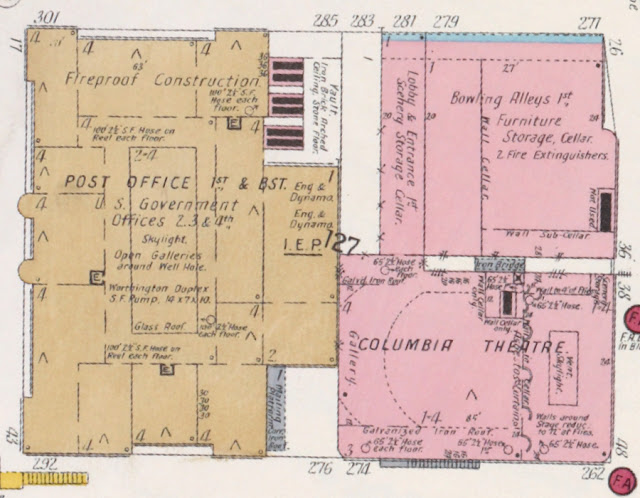

Philip Raqué and Frank Harrison were both engineers, and in 1889 and '90 they both worked at a company called Union Iron Works.1 Founded in early 1889, Union Iron had a factory in Greenpoint and an office at 45 Broadway - a building called Aldrich Court. The company gained distinction for its involvement in putting up the third skeleton frame building in New York City: the Columbia Building.2

The Columbia was twelve stories tall and stretched from Broadway along Morris Street to Trinity Place (just a few doors down from Aldrich Court - both buildings were owned by the Aldrich estate). The plot was long but narrow. As The Sun reported:

To build solid masonry walls in compliance with the laws of the Building Bureau for a structure of that great height would have necessitated walls ten feet in thickness, and thus twenty feet of the ground space would have been required for walls on the basement and first floors, leaving only a little more than nineteen feet of available floor space.The president of Union Iron Works, P. Minturn Smith, convinced the owner of the Columbia lot that skeleton frame construction would be both safe and economical. Thus the building went up in 1890-91, with the walls of "the first story measuring only 2.8 feet."3

Skeleton frame construction was slowly adopted in the city over the next several years, and it was a method used regularly by Atlas Iron. Philip Raqué and Frank Harrison seem to have gained excellent first-hand experience with this practice at Union Iron Works.

The connection doesn't end there, though. The Columbia building was designed by architects William Youngs and William Cable. Incidentally, they had designed Aldrich Court and also had their offices there.

William Youngs was the father of our Frederick Youngs. I haven't been able to find details on Frederick's education or where he was working prior to the founding of Atlas Iron. It's possible that he worked at his father's firm, where he could have been closely involved with the Columbia building as well, and would have known Philip and Frank. Even if he didn't work there, he might have known those men and that project.

I wonder if there was any further connection between these men. Perhaps William Youngs had been a client of Henry Williams during his days as a stock broker, for instance. Perhaps Henry simply met the other men through his cousin-in-law. In any case, he could have dropped by at Aldrich Court in 1890 to meet with two if not all three of the men who would join him in forming Atlas Iron, and they would have been working on and discussing the Columbia Building at the time.

Notes:

1. For Philip Raqué: Stevens Indicator, vol. 6, 1889, p161. For Frank Harrison: Yale University Obituary Record, 1921, p217.

2. "The First 'Skeleton' Building", Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide, 12 Aug 1899, p239. The first skeleton frame building in the city was the Tower Building, constructed in 1889, designed by Branford Gilbert. The second was the Lancashire Insurance Co. building, constructed in 1889-90, designed by J. C. Cady & Co.

3. "New Down-town Buildings", The Sun, 19 April 1891, p27.

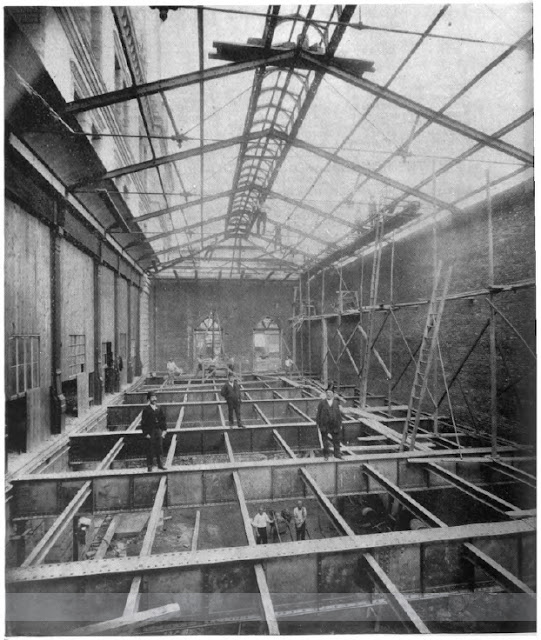

Photo. Excerpt from "Broadway - Morris Street", 1894, from Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.