"He also devised great roof construction for the drill hall of a N.Y. Armory spanning an entire city block. The engineers said it could not be done, so it was quite an accomplishment for our company as the newspapers told the story."This anecdote, more than anything else, is what prompted me to look into the history of Atlas Iron. It conjures a notion of great achievements in building... and it omits the most important piece of information. Which armory did they actually work on?

After a few months of doing research on the company, I found a single mention in a newspaper article which seemed to provide the answer. It stated that they worked on the Ninth Regiment Armory, which was built between 1894 and 1896, on West 14th Street.

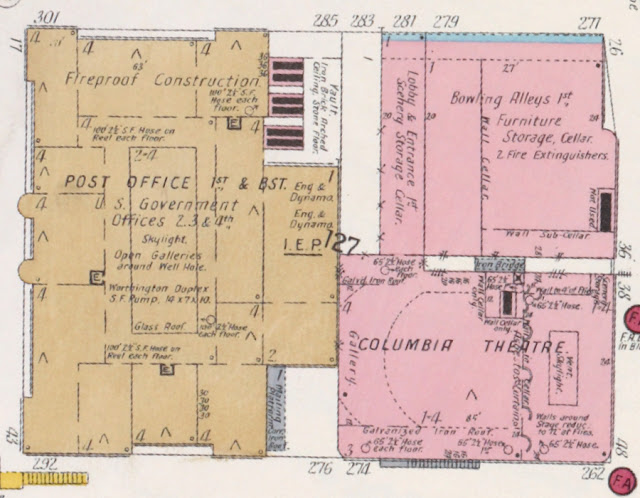

After a long, slow process, a site was chosen on 14th Street. It was in the middle of the block between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, and it ran through to 15th Street. The Twenty-Second Regiment's armory which occupied most of this site was razed to make way for the new building. The Twenty-Second had moved to their brand new armory at Broadway and 67th Street in 1892.

A design competition was held, and the plans entered by the architecture firm of William A. Cable and Edward A. Sargent were chosen. This fact is what makes me fairly confident that Atlas Iron did work on the Ninth Regiment Armory. William Cable had previously been the partner of William H. W. Youngs, father of one of the founders of Atlas, and Atlas Iron worked on several Youngs & Cable projects.

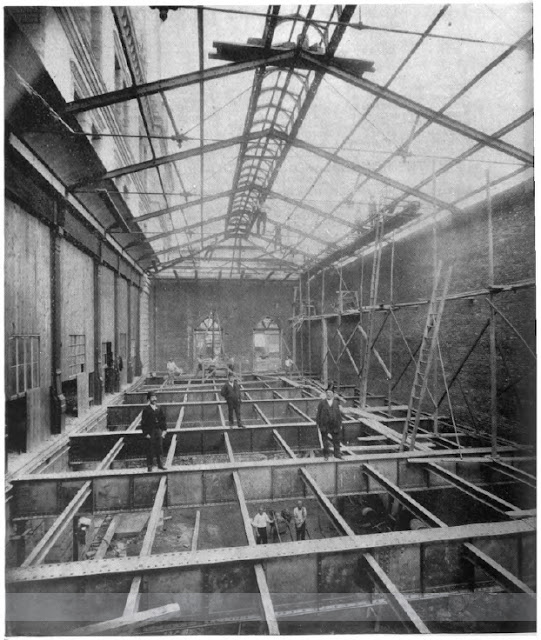

So, what about the impressive drill hall? Sources vary on the exact dimensions, but it was roughly 220 feet long and 185 feet wide (around 41,000 square feet). The center of the arches stood around 64 feet tall. This was not unprecedented. The famous Seventh Regiment Armory, completed over a decade before, has a 55,000 square foot drill hall. Several other armories which were built in and around the city prior to 1894 had similarly large drill halls. I find it hard to believe that engineers would have declared it an impossible feat at that time. Perhaps Fred, who was writing about this in the 1940s, conflated his recollections of Atlas Iron's work and press coverage of the groundbreaking Seventh Regiment Armory. This is not to say that the Ninth Regiment's armory and drill hall did not also deserve - and receive - plenty of praise.

The Ninth Regiment had one of the smallest building plots for an armory in the city at the time, just over an acre (one newspaper said it covered 46,000 square feet). To maximize space for the drill hall on that site, two levels of rooms were suspended between the giant steel trusses, one stacked on top of the other. A skylight was built into the roof.

The armory was completed at the end of the summer of 1896. In addition to military drills, the space was used for civic events; concerts, exhibitions, bicycling, indoor baseball games and other sporting events were all held there. The building stood until 1969, when it was torn down to make way for the Forty-Second Division's new headquarters.

Sources:

Souvenir - Opening of the Armory - Ninth Regiment, N.G., N.Y. (22 Feb 1897).

The Armory Board, 1884-1911 (1912, New York City Armory Board).

Proceedings of the Commissioners of the Sinking Fund of the City of New York (1894-96).

The Sun (New York), 7 Oct 1894 and 4 Sept 1895.

New-York Tribune, 28 Feb 1894 and 8 April 1896.

Family papers.

New York's Historic Armories: An Illustrated History, by Nancy L. Todd (2006). This is an excellent book, if you're interested in learning more about arsenals and armories throughout New York City and State.

America's Armories: Architecture, Society, and Public Order by Robert M. Fogelson (1989).

Daytonian in Manhattan: "The Lost 1895 9th Regiment Armory - 125 West 14th Street".

Exterior photo from Library of Congress (and posted on Daytonian in Manhattan).

Drill hall photo from New York State Military Museum (and included in Todd's book).